The Birth of an Empire

The Aztec Empire, one of the most powerful civilizations in Mesoamerican history, began as a humble alliance of nomadic tribes. Around 1325 CE, the Aztecs, also known as the Mexica, founded their capital city of Tenochtitlán on an island in Lake Texcoco. According to legend, they settled where they saw an eagle perched on a cactus, holding a snake—a vision believed to have been sent by their god Huitzilopochtli.

From these modest beginnings, the Aztecs grew into a formidable empire, using military might, strategic alliances, and an intricate tribute system to dominate much of central Mexico. By the early 16th century, their empire encompassed millions of people and stretched from the Gulf of Mexico to the Pacific Ocean.

The Splendor of Tenochtitlán

Tenochtitlán was the heart of the Aztec Empire and a marvel of engineering and architecture. Built on a series of artificial islands, the city featured advanced infrastructure, including canals, aqueducts, and floating gardens known as chinampas, which supplied the city with food.

At its center stood the Templo Mayor, a massive pyramid dedicated to the gods Huitzilopochtli and Tlaloc. The city was a hub of trade, with bustling markets like Tlatelolco offering goods from across Mesoamerica. Spanish conquistadors, upon seeing Tenochtitlán for the first time, described it as rivaling or surpassing the great cities of Europe.

The Aztec Religion: A Double-Edged Sword

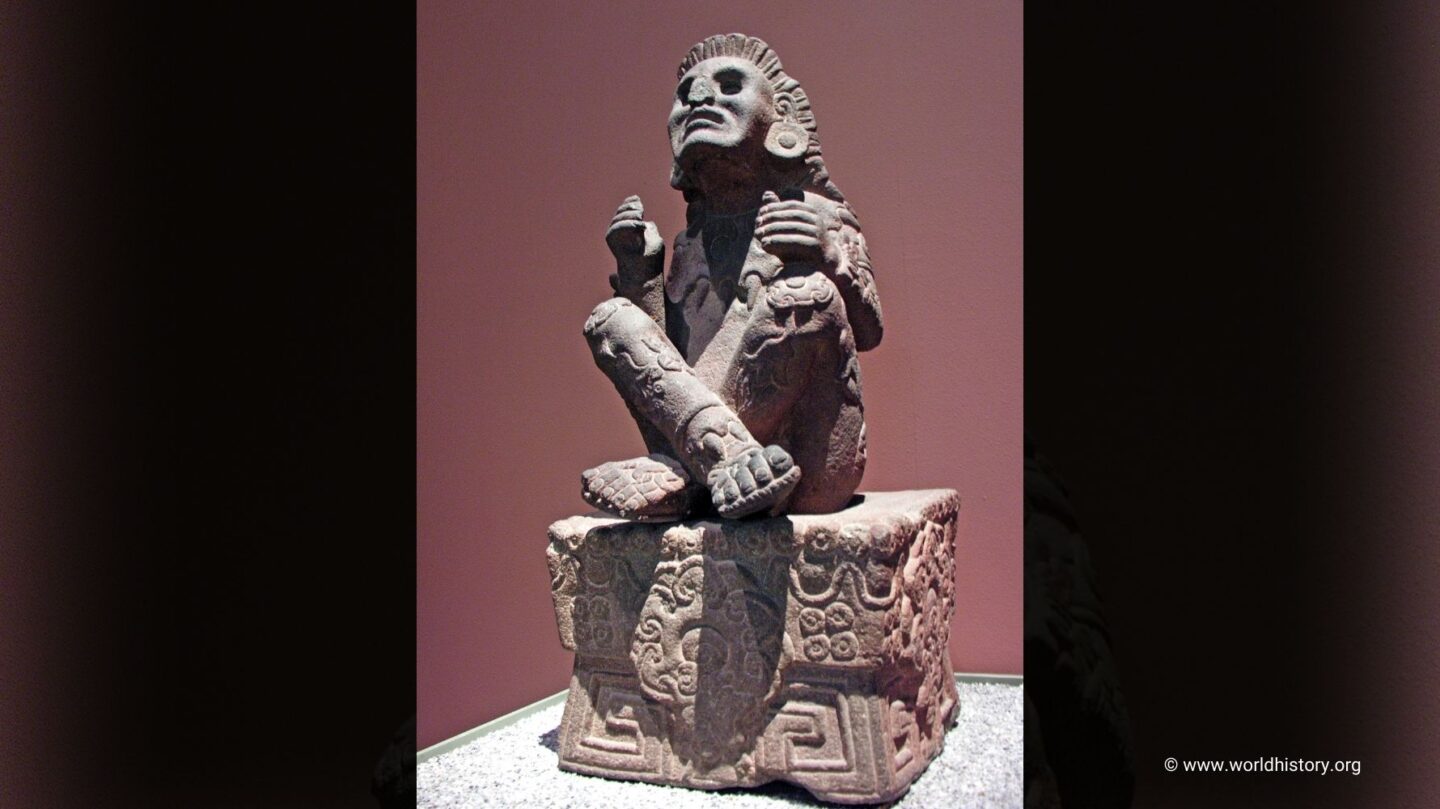

The Aztec religion was deeply intertwined with their political and military systems. They believed in a pantheon of gods who controlled various aspects of life, from agriculture to warfare. Central to their belief system was the idea that the sun god, Huitzilopochtli, needed human blood to ensure the sun’s rise and the continuation of life. This belief fueled the practice of human sacrifice, which became a defining feature of Aztec culture.

While these rituals reinforced the empire’s power and struck fear into their enemies, they also alienated many of their tributary states. The constant demand for captives to sacrifice created resentment among subjugated peoples, which would later play a crucial role in the empire’s downfall.

The Arrival of the Conquistadors

In 1519, the Aztec Empire encountered an unexpected threat: the Spanish conquistadors led by Hernán Cortés. Initially welcomed by Emperor Montezuma II, the Spanish were mistaken for divine emissaries due to their unfamiliar appearance and advanced weaponry.

Cortés quickly exploited the internal divisions within the Aztec Empire. He forged alliances with discontented tributary states, such as the Tlaxcalans, who saw the Spaniards as a means to overthrow Aztec rule. With their combined forces, the Spaniards launched a campaign against Tenochtitlán.

After a series of battles and a devastating smallpox outbreak that decimated the Aztec population, the Spaniards laid siege to Tenochtitlán in 1521. The city fell after months of brutal fighting, marking the end of the Aztec Empire.

The Legacy of Betrayal and Conquest

The fall of the Aztec Empire was not just the result of Spanish military superiority but also of betrayal from within. The alliances forged by Cortés with indigenous groups highlight the deep fractures within the empire. These divisions made it easier for the Spanish to dismantle the Aztec political structure and impose their rule.

Despite its collapse, the legacy of the Aztec Empire endures. Its influence can be seen in Mexican culture, from the imagery on the national flag to the preservation of Nahuatl words in the Spanish language. The ruins of Tenochtitlán, now beneath modern-day Mexico City, serve as a reminder of a civilization that rose to greatness and fell to betrayal and conquest.

A Tale of Triumph and Tragedy

The rise and fall of the Aztec Empire is a story of extraordinary achievements and devastating loss. From the grandeur of Tenochtitlán to the dramatic arrival of the Spanish, the Aztecs left an indelible mark on history. Their tale serves as a cautionary reminder of the fragility of empires and the consequences of internal strife and external threats.